Penmachine

29 April 2010

Ready to move

On Saturday, I'll be switching this blog from the Blogger publishing system, which I've used for almost ten years, over to Movable Type. I've been preparing for the move for a few weeks, and everything is pretty much ready.

What will change?

For you as a reader, not much:

- If you read my posts on my website at penmachine.com, you'll see a few minor alterations to the site layout, but overall things will be familiar. Similarly, if you read them as Notes on Facebook, everything will continue as normal.

- If you subscribe to my blog feed at penmachine.com/index.xml, some recent entries might appear twice, but new ones will only be there once, so it will soon settle back to normal. If you're using one of my older feed addresses (something like penmachine.com/rss.xml or penmachine.com/rss/rss.xml), things should redirect automatically. But if you don't see any updates in the first two days of May, then please re-subscribe using the proper address.

- My Penmachine Podcast feed remains at penmachine.com/podcast/index.xml. Nothing has changed there, and I haven't updated it since July 2009, so don't expect anything new for the moment.

- There will be a new subscription feed for comments on my blog, at penmachine.com/comments.xml, but as of today (April 29), that's not active yet.

Speaking of comments, perhaps the biggest change (which has happened already) is that you can no longer post new comments on any of my archived posts from October 2000 to April 2010, including this very entry. That's not the way I'd prefer it, but in starting fresh with Movable Type, it's just easier to lock down all the old stuff and move on.

You'll be able to post comments on new entries I publish from May 2010 onward. How you do that will look a little bit different than it used to, but will work essentially the same way as before, with a bit more flexibility for you.

Smooth, real smooth

I'm hoping that what is a fairly major technical transition for me is a smooth and barely noticeable change for you many kind folks who read this blog. What should matter to you (at least a little) is what I write, not how I publish it. There will likely be a few minor bumps and anomalies in the first week or so, but I hope to iron those out quickly.

Then I can get on with the next ten years of stuff.

Labels: blog, geekery, history, software, web, writing

28 April 2010

Following the camper

My former co-worker Chris got married to Kerry recently, and they're posting travel photos from their camper-van U.S. honeymoon, which have been great fun to follow. What I especially like is that their wedding presents included sponsorships of various parts of their journey, and they include thank-you printouts in many of the pictures, like this and this.

It's all just terribly charming. I've traveled a lot in the western U.S.A. over the years, especially Oregon and California, so their photos bring back many fond memories. Oddly, I've never visited Yosemite National Park. Maybe someday, if my health improves. Maybe.

Labels: americas, blog, friends, navarik, photography, travel, wedding

26 April 2010

Two more arguments for learning statistics

One of my repeated themes here over the years is how genuinely lousy the human brain is at intuitively understanding probability and statistics. Two articles this week had me thinking about it again.

The first was Clive Thompson's latest opinion piece in Wired, "Why We Should Learn the Language of Data," where he argues for significantly more education about stats and probability in school, and in general, because:

If you don't understand statistics, you don't know what's going on—and you can't tell when you're being lied to.

Climate change? The changing state of the economy? Vaccination? Political polls? Gambling? Disease? Making decisions about any of them requires some understanding of how likelihoods and big groups of numbers interact in the world. "Statistics," Thompson writes, "is the new grammar."

The second article explains a key example. At the NPR Planet Money blog (incidentally, the Planet Money podcast is endlessly fascinating, the only one clever enough to get me interested in listening to business stories several times a week), Jacob Goldstein describes why people place bad bets on horse races.

After exhaustive statistical analyses (alas, this stuff isn't easy), economists Erik Snowberg and Justin Wolfers have figured out that even regular bettors at the track simply misperceive how bad their bets are, especially when wagering on long shots—those outcomes that are particularly unlikely, but pay off big if you win, because:

...people overestimate the probability of very rare events. "We're dreadful at perceiving the difference between a tiny probability and a small probability."

In our heads, extremely unlikely things (being in a commercial jet crash, for instance) seem just as probable, or even more probable, than simply somewhat unlikely things (being in a car crash on the way to the airport). That has us make funny decisions. For instance, on occasion couples (parents of young children, perhaps) choose to fly on separate planes so that, in the rare event that a plane crashes, one of them survives. But they both take the same car to the airport—as well as during much of the rest of their lives—which is far, far more likely to kill them both. (Though still not all that likely.)

Unfortunately, so much of probability is counterintuitive that I'm not sure how well we can educate ourselves about it for regular day-to-day decision-making. Even bringing along our iPhones, I don't think we should be using them to make statistical calculations before every outing or every meal. Besides, we could be so distracted by the little screens that we step out into traffic without noticing.

Our minds are required be good at filtering out irrelevancies, so we're not overwhelmed by everything going on around us. But the modern world has changed what's relevant, both to our daily lives and to our long-term interests. The same big brains that helped us make it that way now oblige us to think more carefully about what we do, and why we do it.

Labels: airport, games, magazines, podcast, probability, psychology, radio, transportation

25 April 2010

A brief visit to the 2010 Vancouver Camera Show

Today was the 2010 Vancouver Camera Show, held by the Western Canada Photographic Historical Association at the Cameron Rec Centre in Burnaby, near Lougheed Mall. I wasn't planning to go, but it turned out that my daughter Marina's new lenses for her glasses, which we got yesterday, were flawed, and needed to be replaced by the optician at that mall, so the two of us were in the area and had some time to kill.

Today was the 2010 Vancouver Camera Show, held by the Western Canada Photographic Historical Association at the Cameron Rec Centre in Burnaby, near Lougheed Mall. I wasn't planning to go, but it turned out that my daughter Marina's new lenses for her glasses, which we got yesterday, were flawed, and needed to be replaced by the optician at that mall, so the two of us were in the area and had some time to kill.

Marina was enthusiastic—she was interested in looking at old Polaroid cameras and to see what the event was like. We walked from the mall, and I paid my $5 admission. (Marina was free.) And wow, it's a heck of an event.

The rec centre gym was filled with dozens of tables with thousands of items of photographic and movie equipment, most of it of some vintage, like the Nikon FE I bought the other day (or a bit newer, or a lot older). Cameras, lenses, flashes, tripods, bellows, enlargers, filters, parts—a photo geek's dream.

It was still very busy, even though we were there barely an hour before closing time. The crowd skews heavily male, and older, but Marina and I had fun poking around at the various obscurities, most in black and chrome, or maybe even leather. I didn't bring much money, nor did we buy anything, yet we hardly noticed the time pass before her glasses were ready and we had to leave. I didn't even take any pictures!

I'll plan to attend again next year, if I'm healthy, and to go earlier. Both Marina and her sister might like to come along, if their photographic interest persists until 2011. Honestly, if I'd gone myself, I probably could have browsed all day. But like a gambler, I'd have to bring cash in advance and set myself a hard limit.

Labels: conferences, family, geekery, meetup, photography, vancouver

23 April 2010

What Darwin didn't get wrong

Last October I reviewed three books about evolution: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish, Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. It was a long review, but pretty good, I think.

There's another long multi-book review just published too. This one's written by the above-mentioned Jerry Coyne (who will be in Vancouver for a talk on fruit flies this weekend), and it covers both Dawkins's book and a newer one, What Darwin Got Wrong, by Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, which has been getting some press.

Darwin got a lot of things wrong, of course. There were a lot of things he didn't know, and couldn't know, about Earth and life on it—how old the planet actually is (4.6 billion years), that the continents move, that genes exist and are made of DNA, the very existence of radioactivity or of the huge varieties of fossils discovered since the mid-19th century.

It took decades to confirm, but Darwin was fundamentally right about evolution by natural selection. Yet that's where Fodor and Piattellii-Palmarini think he was wrong. Dawkins (and Coyne) disagree, siding with Darwin—as well as almost all the biologists working today or over at least the past 80 years (though apparently not Piattellii-Palmarini).

I'd encourage you to read the whole review at The Nation, but to sum up Coyne's (and others') analysis of What Darwin Got Wrong, Fodor (a philosopher) and Piattelli-Palmarini (a molecular biologist and cognitive scientist) seem to base their argument on, of all things, word games. They don't offer religious or contrary scientific arguments, nor do they dispute that evolution happens, just that natural selection, as an idea, is somehow a logical fallacy.

Here's how Coyne tries to digest it:

If you translate [Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini's core argument] into layman's English, here's what it says: "Since it's impossible to figure out exactly which changes in organisms occur via direct selection and which are byproducts, natural selection can't operate." Clearly, [they] are confusing our ability to understand how a process operates with whether it operates. It's like saying that because we don't understand how gravity works, things don't fall.

I've read some excerpts of the the book, and it also appears to be laden with eumerdification: writing so dense and jargon-filled it seems to be that way to obscure rather than clarify. I suspect Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini might have been so clever and convoluted in their writing that they even fooled themselves. That's a pity, because on the face of it, their book might have been a valuable exercise, but instead it looks like a waste of time.

Coyne, by the way, really likes Dawkins's book, probably more than I did. I certainly think it's a more worthwhile and far more comprehensible read.

Labels: books, controversy, darwin, evolution, review, science

Geek office cleanout redux

Almost five years ago, I cleaned out a bunch of old electronics and cardboard from my office/studio downstairs. Yesterday, Earth Day, I got started on it again, this time shipping out four old CRT monitors, two printers, two desktop Macs, an old PowerBook, a couple of keyboards, a scanner, an external CD-ROM drive, a broken camcorder, and a whole mess of wires:

I had an incentive to do it today because, on her way to work, my wife Air noticed a one-day Earth Day electronics recycling event at Killarney Secondary School, which is where I took the heap. It was gone in less than five minutes.

My happiest discard was a drawer full of particularly beige SCSI cables, adapters, and terminators. If you've grown up connecting things to computers with USB or FireWire or Ethernet cables, or using Wi-Fi, be thankful you didn't have to deal with SCSI and its predecessors, which often required flipping tiny switches, swapping cables around, adding thick cable terminators to devices in apparently random combinations, and fiddling with software—and still often didn't work right. Good riddance, SCSI cables:

I felt like Perseus with the head of Medusa there. And yes, I reformatted my hard disks before donating them.

Labels: apple, geekery, green, home, memories, school

22 April 2010

Tumours still shrinking

A couple of months ago, my regular CT scan showed the first-ever shrinkage of cancer tumours in my three-year history with the disease, but I warned that, "I still have cancer, a lot of it all over the inside of my chest, but just a little less of it than I did a couple of months ago." One scan was not yet a trend.

But two could be, and my latest scan showed further shrinkage, with the biggest malignant blob in my left lung going from 3.1 cm down to 2.9 cm in diameter, which means it is smaller than it was in this scan from September:

Some of the others have also shrunk, while other smaller tumours have simply not gotten bigger. The aggressive and sometimes horrific chemotherapy I take every two weeks is doing something. I feel pretty good about that.

I'll remind you that this is not remission, not a cure, not me being "all better." I'm not sure if those things will ever come, and I've already beat the odds on this disease by staying alive as long as I have. What it does mean is that I'm likely to live a while longer yet (whatever "a while" is), which is the most realistic thing I can keep hoping for.

Oh, and happy Earth Day, everyone.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, news

21 April 2010

Back to 1978

A couple of years ago, I bought an old Nikon F4 film camera (introduced in 1988), and I've enjoyed taking pictures with it, especially in black and white. It's a pretty big beast, though, and over time I've been thinking about the first camera I bought for myself in the early '80s, a manual-focus Nikon FG. Then I spotted a surprisingly cheap deal on eBay, and this week it arrived:

It's a Nikon FE, a slightly older (introduced in 1978) and slightly higher-end model than my FG, and it came with a manual-focus 50 mm Nikkor lens. For many years, the electromechanical FE, its companion mechanical FM, and their successors the FE2 and FM2 were often the backup camera bodies of choice for professional photographers—less expensive than the top-of-the-line F2, F3, or F4, but still rugged and simple to use.

Like my F4, this thing feels like a brick, because unlike the digital cameras most people buy today, the FE is almost all metal, including the lens housing. It's also surprisingly small, since it lacks the rubberized covering and big handgrips that digital SLRs like my D90 have. (Since film is out of fashion, the FE also cost me a tiny fraction of the price of the D90.)

Besides my general Gear Acquisition Syndrome and the dirt-cheap price, another reason I bought the FE is that my younger daughter L has been wanting to learn a bit more about photography, and the principles are much easier to demonstrate on an old film camera. With a fixed (non-zoom) lens on it, there are really only three things to adjust: aperture, shutter speed, and focus. DSLRs let you change ISO (sensitivity) and white balance too—among many, many other features—but with the FE those are determined by the film you choose.

I've loaded the FE with some 400-speed black-and-white film, and we'll see how the first photos turn out, and how the photographic experience compares to the F4 and D90. A nice feature of film cameras (despite the inconveniences) is that, whenever you buy new film, you're effectively putting a new sensor inside, so they don't really become obsolete the way digital cameras do.

Labels: cameraworks, family, geekery, nikon, photography

18 April 2010

The Fish House, 45 years later

On Saturday, April 17, 1965, my parents were married in St. Andrews Wesley Church on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver. They held their reception that evening, in a building constructed as the Stanley Park Sports Pavilion in 1930. Today it's the home of the Fish House restaurant.

Last night, 45 years later, also on a Saturday, they returned to the Fish House for an anniversary dinner:

My wife Air, our daughter Marina, and I were happy to join them. (Our younger daughter was at a friend's birthday sleepover.)

I haven't been to the Fish House in at least 15 years, but I won't wait that long again. The food was great—with the added benefit of legacy dishes imported from Vancouver's legendary and recently-closed seaside restaurant, the Cannery. The salmon, prawns, and scallops I ate were excellent, but the rare tuna steak that Air ordered (and which she let me try) was extraordinary.

In August, Air and I will mark 15 years since our wedding in 1995. I hope we can make it to 45, however unlikely my health makes that seem right now. In the meantime, happy anniversary, Mom and Dad. Thanks for inviting us along.

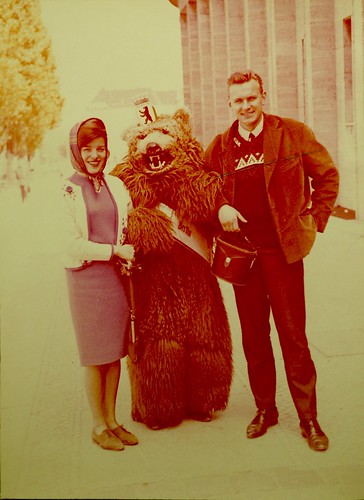

P.S. Here were my parents later in 1965, in Berlin, on their honeymoon:

Labels: anniversary, family, food, restaurant, review, vancouver

17 April 2010

Pretty psychedelic, man

Thank you, Kimli, for finding PhotoTropedelic for the iPhone. It is just too much fun:

Labels: apple, friends, iphone, pets, photography

16 April 2010

Scan and chemo

Today I had yet another CT scan, to see how my various cancer tumours are doing. It probably won't be evaluated by a radiologist for a few days, so it's unlikely to disrupt my next chemotherapy treatment on Monday. But I will communicate soon with my oncologist Dr. Kennecke to find out the results.

Am I nervous? Yes and no. I've been at this so long, having scans every couple of months for over three years now, that I don't find worrying about the results to be too productive. Still, last time the news was somewhat good. I'm a little nervous about that.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, ctscan

15 April 2010

Sunny days at Camp Jubilee

I can almost see the place where my daughter Marina slept last night, and will again tonight. But not quite. She and her school classmates in grades 6 and 7 are at Camp Jubilee for a two-night, three-day outdoor education adventure.

I can almost see the place where my daughter Marina slept last night, and will again tonight. But not quite. She and her school classmates in grades 6 and 7 are at Camp Jubilee for a two-night, three-day outdoor education adventure.

The camp sits near the tiny shoreline community of Frames Landing (which I'd never heard of until I looked it up just now) on the west shore of Indian Arm, the fjord whose mountain boundaries I can see from my front window. But those mountains are so steep and packed together that, though the camp is closer to our house than the ski slopes of Grouse Mountain that we can see clearly every day, it is entirely hidden behind several tree-coated ridges.

The only way to reach Camp Jubilee (or the homes at Frames Landing) is by boat. The camp has one to ferry visitors back and forth from Deep Cove, the urban harbour about 15 minutes to the south that is the easternmost part of North Vancouver. The kids have been incredibly lucky this week: the weather has been sunny and unusually warm, and looks to remain so through tomorrow when they come back.

I'm sure they've had a great time, and Marina will be pooped when I pick her up at school in the afternoon. Her younger sister will be returning from her own day trip with her classmates snowshoeing on Grouse Mountain. I expect they'll be a couple of sleepy girls come Friday night.

Labels: environment, family, school, vancouver

14 April 2010

Movable Type vs. WordPress, Round 2

A bit more blogging platform geekiness, but much shorter this time.

Contrary to my first impressions a couple of days ago, I'm warming to the way Movable Type works. It's taken only a little effort to customize it, roughly to match my existing page design and typography here—easier than I've experienced with WordPress.

So, two days later, it looks light I might end up using Movable Type 5 after all. But we'll see if my further experiments blow it up in some nasty way.

Labels: blog, geekery, linkbait, software, web, writing

12 April 2010

Replacing Blogger: Movable Type vs. WordPress

This is a big long nerd brain dump about behind-the scenes software stuff on this website. Even if you're not a web geek, there's a possibility you might find some of it interesting. But if not, you've been warned.

UPDATE: A couple of days later, I may have changed my mind about my apparent decision below. Find out more.

Gotta move

Since Blogger announced the shutdown of its venerable FTP publishing system a couple of months ago, I've been working to figure out what new system I'm going to use to publish my writing here. (I'm glad Blogger postponed the shutdown for an extra month, but of course that meant I simply procrastinated about it until now.)

I have about three weeks to make the change, and I've boiled it down to two options, neither of which is ideal, but both of which are serviceable:

- WordPress (currently at version 2.92), a PHP-based system, with the Really Static plugin.

- Movable Type, written largely in the Perl programming language (currently at version 5.01).

They are two of the most popular and long-running blogging platforms on the Web. There are other possibilities, but I don't need all the complexity of Drupal, and don't find other options like ExpressionEngine all that compelling. Movable Type has always used the static files publishing model I prefer, while WordPress requires a plugin like Really Static to hack it into doing what I want.

Movable Type in the sunset?

However, Movable Type's day in the sun may be past. While some high-profile sites of people I know—such as John Gruber and Dave Shea—use it, its popularity seems to have been in general decline since the licensing controversies of version 3, way back in 2004. The current version 5 (MT5) is brand new, and an open source project, but I don't sense the same community vibrancy and wealth of third-party extensions WordPress has. Six Apart, the company that created Movable Type, also seems to have been focused on its other hosted blogging tools, TypePad and Vox, for years.

There's a fork of Movable Type called Melody too, which is cool. But forks like that tend to arise when the originating platform is losing air. Yes, I know there are lots of people who love it, but I just get the sense that general enthusiasm for Movable Type has faded—even in the vibe I feel after installing and playing around with MT5 last night. The basic software is great, mature, and solid. But when I want to muck around and extend it, the available resources are a little sparse and often out of date.

WordPress on a tear

Just when Movable Type stumbled in 2004, Matt Mullenweg's WordPress—itself a fork of the awkwardly-named b2/cafelog blogging platform—was hitting its stride. I know Matt a bit, and have been using WordPress on other websites (most notably Inside Home Recording and Lip Gloss and Laptops) since 2006. I like it and recommend it to friends, despite its sometimes-sprawling nature, and its reliance on a dynamic, on-the-fly, database-driven publishing approach that I find somewhat brittle.

Indeed, that dynamic approach really was the only thing keeping me from switching to WordPress right away. I understand WordPress and how to tweak it, I like the wide range of themes and plugins available for it, most of my geek friends use it in some form or another, and the community is second to none. Recent versions are also very easy to upgrade in place, which is a big improvement over the way most installable blog platforms (WordPress and Movable Type included) have usually worked.

So when Matt Mullenweg's colleague, Victoria-based Lloyd Budd, pointed out the Really Static plugin to me, it looked like a perfect solution. It takes a regular WordPress blog and generates plain-old text files which otherwise continue to look and work pretty much just like the original WordPress pages. Nice.

The showdown

Therefore, last night, after all that procrastinating and evaluating, I installed both WordPress 2.9.2 (with Really Static) and Movable Type 5.01 into test directories on my server. The WordPress install went smoothly, since I've done it before. Movable Type took a couple of tries, but I got it working without too much trouble. Disabling either software installation seems to leave the resulting static blog pages essentially intact, which, after all, is my key criterion in this whole production.

As I said above, I found Movable Type underwhelming. I really, really wanted to like it, because it would be interesting for me to learn how to work with and tweak a new publishing system. The default appearance theme is certainly nicer than WordPress's, and its more modular system of templates and styles is also a bit more elegant. Though not a key feature for me, it's much easier to publish multiple blogs with a single Movable Type installation (at least for now). Some tech-head friends I respect a lot think its Perl-based CGI architecture is inherently better than WordPress's collage of PHP scripts.

All that may be true, but MT5 looks, to me, like it's catching up to features and polish that WordPress has offered for at least two or three years. Searching for some alternative themes and styles, as well as fairly simple plugins (displaying my recent Twitter posts on my home page, for instance), didn't yield very many options, and most of the results I did get seemed to be talking about MT installs a version or two old.

Not that the WordPress option is perfect. The forest of PHP files that WP uses can make heavy customizing kind of a chore ("which of those 250 files was I supposed to edit again?"). The Really Static plugin remains a hack, though an effective one, so making it do what I want requires some duplication of template files, some advance planning of how I want to structure my blog and archives, careful pruning of HTML pages on the server if I choose to delete something, and the awareness that when WordPress releases a new version (like the upcoming 3.0, or even a service update like 2.9.3), I might have to wait to make sure Really Static plays nice with it.

So right now, I'm leaning heavily toward the WordPress/Really Static approach [but wait! see my April 14 post to find out if I changed my mind]. Any Movable Type advocates (or people with different suggestions) who want to convince me otherwise can email me or leave a comment here—at least until I disable comments on this post at the end of the month (see below).

Other housekeeping

One annoying thing about moving away from Blogger as my publishing system is that I'm going to have to lock down my blog archives. What I mean is, I'm not planning to import all my nearly 10 years of existing blog posts into the new system and republish them. Indeed, one of the advantages of the static-files approach I'm choosing is that I can just leave my old posts exactly as they are, whether from 2001 or 2009.

But since I'll no longer be able to update the pages from Blogger, that also means that no one will be able to post new comments to those posts—or, more accurately, if I leave things as they are, people can write comments, but they'll never show up on this website. So my plan, over the course of the next three weeks, is to disable new comments on my old posts, and gradually disable them on newer and newer ones until FTP publishing stops working at the end of the month. Then, if I time things right, I can seal off comments on my latest entries, tie up the old blog in a bow, fire up the by-then-ready new system, and be done.

I've already started. Want to comment on one of my posts from April 2007 or earlier? Sorry, you can't. Same for entries for my occasional Penmachine Podcast from last year or before. They were never much for comments either.

Yeah, it's a bit of an awkward transition, but after a decade of largely smooth sailing with Blogger, I can hardly expect anything else. I'll miss the simplicity and familiar orange-and-blue colour scheme of writing in Blogger, but I won't miss its bizarre system of labels, its strange way of handling podcast enclosures, and of course the consistent unreliability of FTP publishing in the first place. Besides, for the geek in me, making the change is sort of fun.

As long as I don't screw anything up too badly over the next few weeks, anyway.

Labels: blog, geekery, linkbait, software, web, writing

09 April 2010

Buzz time

Once again, chemotherapy is doing bizarre and nasty things to my hair. It's thinning, while getting wiry and bushy and annoying. But rather than do the full Peter Garrett shave as I did two years ago, I went for my preferred buzz cut again:

My "before" look on the left was about as as good as I could make it appear, but there was still something vaguely Kim Jong-Il about it. I prefer the shorter version on the right, and I'll try to keep it that way.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, photography

What does it mean to be old?

New Scientist has published a widely-linked article (via Kottke) this week called "The Shock of the Old," about how the world's population is aging. Author Fred Pearce is perhaps a bit too optimistic about what that means, but it's nevertheless a worthwhile read. It reinforces something I've written about before. As Pearce puts it:

We should be proud that for the first time most children reach adulthood and most adults grow old.

But old doesn't mean what it used to. I regularly hear news reports about an "elderly" person of age 70. But that's how old my parents are, and they don't seem at all elderly to me. Yes, my mom retired some years ago, but that doesn't seem to have slowed her down. My dad is still running his own business and driving to service calls almost every day. He'll happily climb a ladder to the roof of the house to clear out the gutters.

And of course, these days they're both in better shape than I am, at age 40.

I think societies like Canada's, where our population is aging rapidly, will have to adjust, to support people based not on the number of years they've lived, but on the capabilities they have. In some ways, we already do that—I'm receiving Canada Pension disability benefits, for instance. I don't know what that adjustment will look like, and I may not even live long enough to see the change, but it's coming.

Labels: age, canada, death, history, magazines, work

08 April 2010

Another relative

It's quite astonishing how many fossils of extinct human relatives that paleontologists have found in recent years. Just in the past year, I've mentioned Darwinius and Ardipithecus. And this week we hear about Australopithecus sediba, which sheds further light on how ancient apes transitioned to walking upright like we do.

It's quite astonishing how many fossils of extinct human relatives that paleontologists have found in recent years. Just in the past year, I've mentioned Darwinius and Ardipithecus. And this week we hear about Australopithecus sediba, which sheds further light on how ancient apes transitioned to walking upright like we do.

It's a relief that in the latest coverage, the scientists involved have gone out of their way to say that A. sediba is not a "missing link":

"The 'missing link' made sense when we could take the earliest fossils and the latest ones and line them up in a row. It was easy back then," explained Smithsonian Institution paleontologist Richard Potts. But now researchers know there was great diversity of branches in the human family tree rather than a single smooth line.

All of evolution works that way: branching, somewhat messy relationships between organisms, with many extinct species and a few (or perhaps many) survivors. In the case of hominids, we humans are the only bipedal ones left, and we're also by far the most numerous of the surviving lineage, which includes chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans too. So our evolutionary past can look linear, at least during the past 5 to 7 million years since our ancestral line diverged from the chimp ancestral line, even though it wasn't.

While we have found quite a few fossils of human relatives, that's a very relative term. Until the past few thousand years, there weren't many of us around at all. All the Australopithecus fossils ever found can be outnumbered by the number of trilobite fossils (which are hundreds of millions of years older!) in a single chunk of stone at any rocks-and-gems store. Hominid fossils are still extremely rare things, so we can't reconstruct the branches of our family tree with perfect accuracy. That's because we can't be sure which (if any) of the species we've unearthed were our direct ancestors, and which were our "cousins"—branches of the tree that died out.

Still, we can make attempts with the data we have, some making more assumptions than others, and the options being quite complex. Yet as we find out more, and discover more, our family tree becomes clearer. That's pretty cool.

Labels: africa, evolution, history, science

07 April 2010

My first microwave experience

The first time I ever used a microwave oven was at my friend Brent Spencer's house, sometime in the mid-1970s. I'm pretty sure it was an Amana Radarange. Brent's father Ken, who would later go on to found the digital printing company Creo, is an engineer, and often had interesting gadgets well before the rest of us got them.

(Some examples: Ken borrowed a projection television for a few weeks, which I got to watch in their basement; was the first person I knew to have a phone in his car; and loaned us their family's TRS-80 microcomputer while they went on a long vacation in 1980.)

Anyway, the first thing Brent showed me how to make in the exotic Radarange was Triscuits with Kraft process cheese slices melted on top. I stared in wonder through the oven window as the cheese rose into what seemed like an impossibly big bubble, then popped into a goopy mess. Delicious.

Recently I did the same thing: 30 seconds on high power, with Triscuits and Kraft slices. You know what? They still tasted great.

Labels: age, food, friends, geekery, memories

04 April 2010

How did it get here?

A desiccated fruit husk, about 5 cm long, sat delicately on a nearby lawn this afternoon. I spotted it while walking the dog:

Did dry out like that naturally? I've seen similar veins-only leaf skeletons around, but this seems much more fragile:

I wonder what kind of fruit it was, and how it got there.

Labels: biology, photography, vancouver

03 April 2010

Strat-o-glasses

A few weeks ago, when I bought my new eyeglasses, both my wife Air and my daughters' piano teacher Lorraine independently said that one pair—my set of black Ray-Bans with pearloid decorations on the sides—strongly resembles a Fender Stratocaster guitar, like the black and white one I own. I didn't notice it when I picked the specs, but they're quite right:

In this photo, I also bear a frightening resemblance to Vince the ShamWow guy. That too was entirely unintentional, believe me. (Though maybe I can make America skinny again, one chord at a time!)

Labels: celebrity, glasses, guitar, music, photography, television